The showrunner Tony Gilroy said he was not a fan of the Star Wars series. However, as one of the best script doctors in Hollywood, he got roped into fixing up "Rogue One" and subsequently was given the (I'm sure a lot of) money to do the spinoff series "Andor" for Disney's streaming business.

Nevertheless, the relatively dark and menacing "Andor" series caused me to revisit the contradictions in the heart of George Lucas' original Star Wars series. Critics have commented that "Andor" is tonally different from the SW franchise and more "adult" in its depiction of war, police state, oppression, the prison-industrial complex, and revolution.

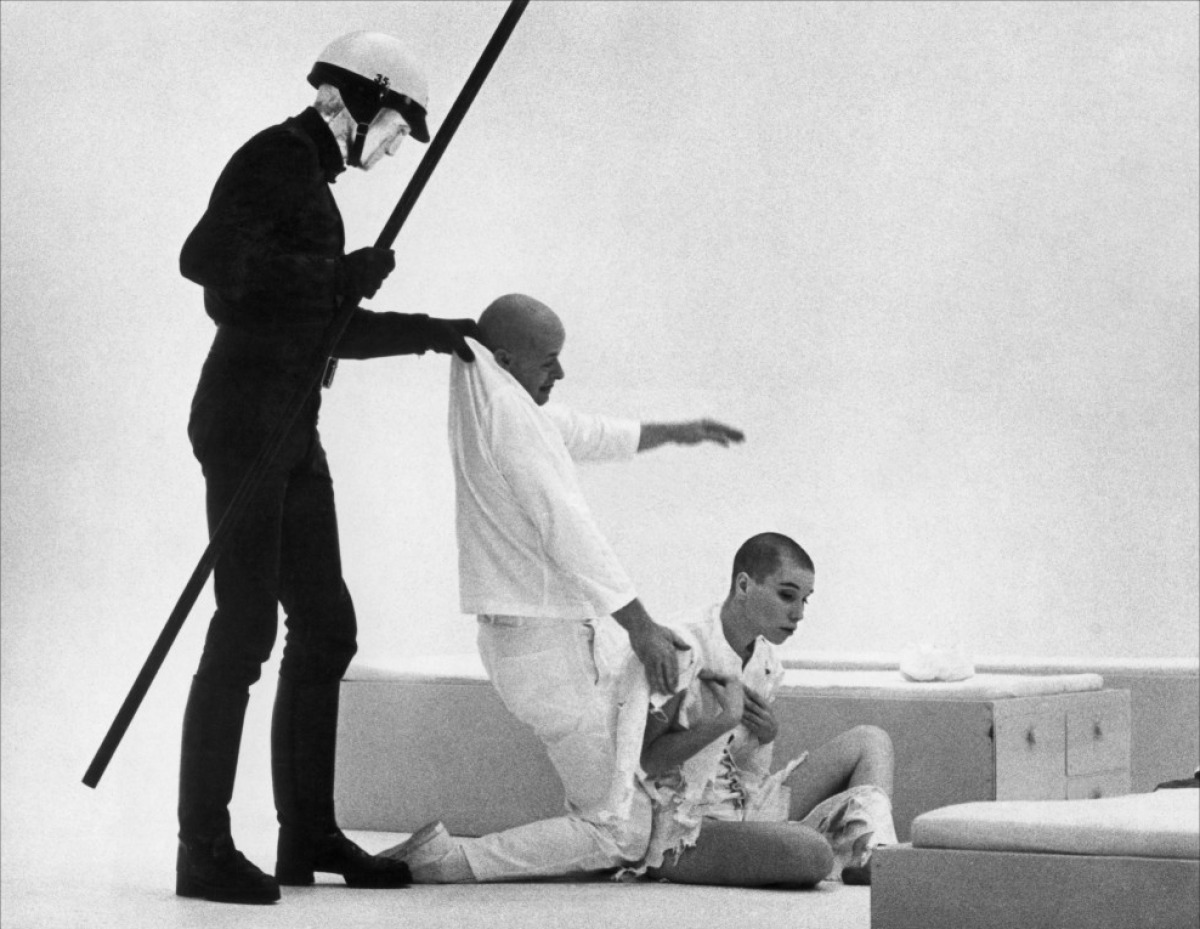

For example, the torture scene is quite disturbing in "Andor", even though it is much less graphic than the scene in "The Last Jedi," but we should not forget that there was also one in A New Hope, in which Princess Leia was tortured by Darth Vader (who turned out to be her father, think about that symbolism for a moment) with no apparent effect afterward. (Yes, when they want to show an entity is evil and to induce sympathy and outrage, the go-to device is that they torture and rape/kill women. Everyone knows the trick.)

Another example of parallel plot is how a reluctant central character makes the decision to join the rebellion. Does anyone still remember the turning point of Luke Skywalker? The imperial troopers killed Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru. Similarly, it was only when his mother Maarva had died that Andor decided to stop running from his destiny. His father had been executed by the Empire years ago. Of course Maarva was not directly killed by the empire, but it was close enough.

So my argument is that Gilroy was really trying to hew pretty close to the original SW, which is pretty dark and sinister if you look closely. And yet, the series also "disneyfied" itself from the start, making it palatable to the American mass audience. It was Lucas' conscious decision to make the deaths completely bloodless, when SW was financed by 20th Century Fox. Hell, the dead characters even come back as smiling, approving ghosts (a device cleverly echoed but not exactly endorsed in "Andor" with the holographic recording of Maarva).

This manipulation cannot be blamed on Disney's production of episodes 7 to 9, unless we consider the decades-long effect Disney had had on the American popular culture since it started to convert dark and vicious folktales into cute cartoons. I was struck, in "Attack of the Clones", how indifferent and meaningless the action scenes were, because the killing was enacted upon thousands and thousands of fleshless droids. There is no feeling, no stake, and nobody cares. But it was intentional to protect the audience from seeing any blood and real death.

We should also consider the contradiction at the heart of SW. What is the empire an allegory for? Commentators and the public assume that the empire refers to the British Empire and the rebellion the American revolution --- All the imperial characters spoke with an English accent while the heroes spoke with an American accent, and that's no accident. Sometimes Lucas tacitly approved of this interpretation, but occasionally he said openly that ROTJ is an allegory of the Vietnam war, implying that the empire is the American one. Nevertheless, he took care not to be too loud about it.

I gotta hand it to his sophisticated manipulation. George Lucas is the best case of "having his cake and eat it" that I have ever seen. This is how you do it, baby! We do not need to worry that the audience may recognize themselves in the evil empire (and some actually do so). Contrary to the logical awareness "Are we the baddies?", the human instinct shields people from such uncomfortable reflections, and everyone believes he is one of the good guys. Besides, Ronald Reagan told everyone who the evil empire was --- those guys over there!