To this day, the public generally believes that the reason for the death of Sherlock Holmes in "The Final Problem" was that Arthur Conan Doyle was tired of writing these stories and wanted to stop, and the reason for its reversal in "The Empty House" was the unending pressure from fans on the author.

However, David Pirie (who wrote "Murder Rooms" starring our Dr. Doyle and his mentor Professor Bell) questioned this oft-repeated theory and pointed out that Doyle went on a Holmes hiatus for a long 8 years. If public pressure was the reason for his reversal, he would have done so in the first year or two, when the outcry was the loudest. It is hard to imagine that the public was still pressing him to revive Holmes 8 years after the death, so much so that he caved under the pressure to write one of the best entries in the collection, "The Hound of the Baskerville." Pirie also pointed out that Doyle wrote the story in 1893, about the same time his father died, which might have been a dark and painful event.

I recently re-read "The Final Problem" and "The Empty House." There are many peculiar elements surrounding the death and resurrection of Sherlock Holmes, which convince me that the conventional wisdom is, if not entirely wrong, at least missing the point. I tend to agree with Pirie that the story is associated with some emotional clouds on Doyle's mind. If he wanted to stop writing Holmes stories, he can just stop writing them without killing Holmes. The death is about death, not merely a callous middle finger at his fans.

Where Is the Body?

The first question is, if the Sherlock Holmes fanbase flooded the publisher's mailbox demanding that Doyle bring him back to life, whose fault is that? Can you blame them for thinking that Holmes was still alive, because there is no body? Naturally, one has to wonder, Why isn't there a body? Surely ("Don't call me Shirley!" to quote Leslie Nielsen), if Doyle really wanted to kill off Sherlock Holmes, he could have at least produced a body in the river, somewhere downstream from the Reichenbach Fall, and give Holmes a proper burial.

So, the only explanation is the simplest. Doyle did not truly intend to kill off Holmes. I doubt he consciously planned out the details of how to bring him back later, but a part of his mind must have left open a backdoor for the possibility of revival.

In other words, the ending of The Final Problem is meant to be ambiguous. Even if he did not know whether he would write another Holmes story ever again, he did not want to give us, or himself, Holmes' corpse. I also suspect that he at least had a vague idea about the escape route, ie, scaling the cliff, just in case he wanted to bring Holmes back to life. Perhaps he didn't even expect to wait as long as 8 years.

Why Do They Leave Britain?

The general theory is that Doyle was impressed by the natural beauty of Meiringen during a vacation, also in 1893, and decided to place the climax to the story there. However, the way the story takes Holmes and Watson there is decidedly bizarre and uncharacteristically nonsensical.

In the first half of the story, Dr. Watson (and hence the reader) was dragged by Holmes on a fast and furious trip from London to France, and from France to Belgium, and then onward to Switzerland, in order to escape the assassination attempts by Moriarty's criminal organization (as Holmes claimed). However, Holmes also told Watson that he needed only 3 days to stay alive and wait for the police to arrest everyone in the organization. Three days was all.

"In three days--that is to say, on Monday next--matters will be ripe, and the Professor, with all the principal members of his gang, will be in the hands of the police."

When Holmes said the above lines to Watson, it was obviously Friday. They went to Victoria station the next morning, which must have been Saturday. So, he needed only to pass the weekend without being killed.

To buy 2 days of safety, he had to run all the way to the continent? That makes no sense. I can think of a dozen solutions to Holmes' dilemma. For example, he could call in a favor with the Scotland Yard to assign a few policemen to him in a hotel across the street from the headquarters. Or he could use the incredible makeup and acting skills and hide out in an opium den, like "The Man with the Twisted Lip." Or he could hang out for 3 days inside the Diogenes Club, which was, supposedly, next door to Whitehall. He could even hide out in the Whitehall for 2 days, since it was the weekend anyway. Even if he had to play cat and mouse with Moriarty on the road, he could have gone anywhere on the British Isle, from Wales to Scotland. Why did he have to cross the Strait? Was Doyle too lazy to make up an excuse for the long journey?

Despite the meticulous instructions for Watson to shake any tail, they were still followed at the train station toward ... presumably Dover, then boat, then Calais, then Paris. The destination is confirmed a couple of pages later:

"Moriarty will again do what I should do. He will get on to Paris, mark down our luggage, and wait for two days at the depot (emphasis mine)."

Why did he expect Moriarty to wait for 2 days in Paris? Two days later, ie, on Monday, if he were still in Paris, he would not be arrested "with all the principal members of his gang," would he? And, indeed, that was exactly what happened. On Monday, in Strasburg, Holmes telegraphed to the London police and received a response, to which he made a most unconvincing reaction:

"They have secured the whole gang with the exception of him. He has given them the slip. Of course, when I had left the country there was no one to cope with him."

Right. So why did you leave the country in the first place? Besides, did Moriarty escape the police or was he still in Paris, waiting for the arrival of Holmes and Watson?

Again, the only explanation is the simplest. Holmes was not trying to escape Moriarty but rather lure him to the continent. The reason he left Britain was to make sure that Moriarty is not arrested on Monday with the rest of his gang.

Why Not Go Home?

At this point, I'm sure you are wondering, why would he do that? Why go on this journey abroad just to cause Moriarty to unknowingly escape the British police?

But let's first look at another baffling choice here. Now that the arrests had happened and the gang was behind bars, Holmes decided to go on to Switzerland. Was he still trying to outrun Moriarty? (Even though he, obviously, never did try to outrun Moriarty in the first place.) No.

"This man's occupation is gone. He is lost if he returns to London."

So, if Holmes wanted personal safety, he only needed to go home, since Moriarty could never return to Britain legally. He even suggested that Watson go home. Then why not go home together but rather head toward Meiringen?

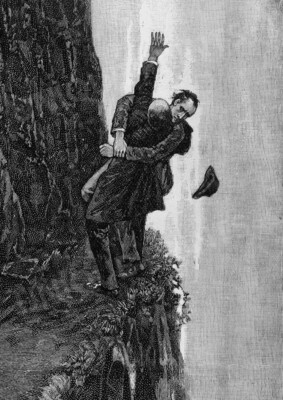

The narrative from Strasburg to Meiringen is even more transparent that Holmes was baiting Moriarty, leading him to a particular location. On the dead-end path by Reichenbach Fall, Holmes went as far as admitting that he knew the message to Watson was fake and devised by Moriarty to attack him.

The simple explanation is that Holmes orchestrated the entire journey in order to get Moriarty to this place, alone, for a violent confrontation. In other words, Holmes had always planned to kill Moriarty here, far away from the British authority.

In many other stories, we have seen Holmes circumvent the law to let a criminal, even a murderer, go. He has shown at least a moderate degree of cynicism or distrust for the official legal system. I have no doubt the stories would have been much darker and more cynical, if Doyle had not tried to protect the public's sense of morality and belief in authority. Here, however, I am sure he knew that personal vigilantism was one step too far for his Victorian readers.

On the trip Holmes made a number of oblique remarks to Watson that sound like suicide notes, almost as if he had foreseen his own death together with Moriarty. However, if we read this part again, we can also interpret these as not biological but rather career suicide, and it sounds like protestation for his professional reputation:

"If my record were closed tonight I could still survey it with equanimity. ... In over a thousand cases I am not aware that I have ever used my powers upon the wrong side. ... Your memoirs will draw to an end, Watson, upon the day that I crown my career by the capture or extinction of the most dangerous and capable criminal in Europe (emphasis mine)."

Why Send Watson Away?

This is never explicitly stated in the story, but the tone suggests (very vaguely, if I may say so) that Watson believed that Holmes knowingly sent him down the mountain in order to protect him from any risk of injury or harm by Moriarty. Or perhaps the Victorian readers assumed that Holmes adhered to the medieval battle code of duels, mano-a-mano. If Holmes were merely waiting for Moriarty to come at him so that he could arrest him alive, wouldn't it make sense to keep Watson around with his army revolver? Holmes never let any medieval machismo prevent him from recruiting Watson's help on apprehending criminals on other cases before.

When I presented this question to a generative AI, it replied that, besides protecting Watson, Holmes wanted the world to believe he was dead, implying that somehow Watson could not keep a secret. We saw him play a similarly cruel trick on his old friend. However, that story was written in 1913! In 1893, when Doyle wrote this story, Holmes was not supposed to pretend to be dead ... or was he?

If Holmes really wanted to merely capture Moriarty, surely ("Don't call me Shirley!") a two-on-one confrontation is a much better bet. The only possible explanation for knowingly sending Watson away is to remove any witness of his illegal action next, which is ... more on that later.

And, of course, removing Watson also serves the purpose of keeping Holmes' fate open-ended. Otherwise, Doyle could have written a scene in which Watson came back just a smidge too late, watching both Holmes and Moriarty plunge into the abyss ... but he did not.

What Actually Happened?

There is no way of knowing what Doyle actually intended to do with the duel between Holmes and Moriarty. However, as I argued above, he did not want to definitively kill Holmes. The situation is in fact very similar to the final problem of Hecule Poirot, where the detective did play the vigilanti and kill the bad guy. In that case, however, Poirot was driven to definitive suicide by his own conscience. This is certainly one possibility for Holmes ... maybe? The question is whether Doyle respects the standards of justice as much as Agatha Christie. I don't know the answer.

However, in 1903, Doyle gently soothed readers' sense of justice by portraying Holmes' survival and the killing of Moriarty as a fair fight in self-defense. This trick continues to be used in today's movies and thrillers. The good guy does not mean to kill the bad guy, but, oops, he killed the bad guy accidentally or unintentionally. All of our conscience is safe.

Alternatively, since Doyle left the door open for himself, I can also imagine the final fight scene, in which the well-prepared Holmes pulled out a knife, maybe from his walking stick that got mentioned so many times, and stabbed Moriarty as soon as the latter got close enough, or perhaps pulled out his own revolver and shot the professor on sight. Then he calmly threw the body into the abyss.

That would probably have lost him a bunch of fans, but I kind of like it.