I don't need to dwell on the many wonderful qualities of this 2021 movie, except that the single most effective choice made by the director (Ryusuke Hamaguchi) was to cast a deaf actor as Sonia in Uncle Vanya, the play within the movie. It is absolutely ingenious and perfect. I don't know how other people feel about the extensive enactment of "Uncle Vanya" and use of its lines to suggest the characters' state of mind throughout the movie. For me, who recently read the play and watched 2 other movies based on it, the power of Chekhov is immense. It is unmistakable that Hamaguchi feels the same way.

Nevertheless, I want to touch on a particular aspect of the movie that is unsatisfactory to me. Spoilers abound below.

After watching "Drive My Car," I went and read the original short story by Haruki Murakami and a couple of other stories in the same collection, Men Without Women, that contributed minor elements to the movie. I have not read any of Murakami's novels, but one cannot escape his cultural influences. I read his “Barn Burning" after watching Lee Chang-Dong's adaptation, the 2018 movie "Burning", which left little impression (unlike the movie). None of his short stories resonated with me (quite the opposite of Chekhov).

One of the things that has bothered me from the start about Murakami's works is his (ab)use of deaths, often in female characters and sometimes suicide, as a crutch in service of the male character's emotional state. There is a similar phenomenon in English-language popular culture that, by now, has been well established, ie, female characters die in order to bring about the spiritual growth or maturity of the (male) hero. Fundamentally, I think Murakami's tendency is not that different, but it might seem a little different to western critics because of the pervasive sense of melancholy in Japanese arts and culture. Death evokes a kind of beauteous sentimentality about the fleeting nature of life and all good things. That in itself is fine, but excessive use with a callousness can trivialize death as a dramatic device and obliterate its meaning.

The flip side is another convention in Japanese popular culture, based on my limited exposure: the trope of life affirmation. I have lost count of Japanese movies and TV series in which characters tell each other or themselves with a loud declaration: "I/you/we must go on living!!!" (At least 3 exclamation marks!) Implied in the declaration is that living takes too much effort and death is the default position.

Putting aside the rightness or wrongness of this philosophy --- who am I to judge? --- I am merely pointing out that death and "pushing oneself to keep on living" are two tropes in Japanese popular culture. I don't know how the average Japanese people in real life feel about it, as I don't know any Japanese person in real life. Maybe they don't give a fuck and enjoy life just fine.

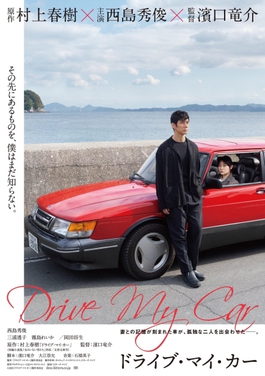

Coming back to "Drive My Car," the theme is the difficulty for people to connect with each other, even between couples in love or parents and children. The main character is haunted by his inability to talk to his wife about her having sex with other men; now it's too late to understand because she died suddenly. The driver is haunted by her guilt over the death of her abusive mother. The two lonely people, damaged by the death of their loved ones, connect with each other in the little red Saab. The climactic scene, when the main character expresses his regret for his avoidance of talking to his straying wife when she was alive, did not have the expected effect on me. Instead, for me, it was a moment like, "Isn't it ironic, don't you think? A little too ironic..."

The main character had repressed his feelings about his wife's infidelity and maintained the pretense of a happy marriage, because of his fear of the confrontation with his wife and possible dissolution of their marriage. That part is obvious. So then, isn't it convenient that she is dead? Her sudden and random death is, symbolically, his (the author's) wish fulfillment. Her death removes the threat of being exposed to an intolerable reality --- that she is a real person with her own thoughts, feelings, desires, and intentions, which may not align with his. Maybe she doesn't love him any more. Maybe she prefers other men to him. Maybe she will leave him.

One could extend this argument to the movie itself. After observing these two characters gently and compassionately for over 2 hours, it successfully avoids the hard stuff: a painful self-discovery, both of the main character's insecurity about his manhood and of the driver's hatred for her mother and her desire for separation. Also avoided is the characters' aggression toward the people they love. Their anger and resentment alongside love and attachment. Their fear of rejection and abandonment. All the difficult and terrifying honesty is swept under the rug of a rote declaration, "We must go on living!" The end.

The truths in life must be avoided at all cost (eg, love exists alongside hate, we all have aggression, attachment cannot be permanent, we are not the center of the universe). In comparison, death is an easy escape from painful confrontations. Hence we can see how these tropes are so irresistible to dramatists. That is why we all need to go back and read Chekhov again.

No comments:

Post a Comment