Books, movies, food, and random thoughts in English and Chinese. Sometimes I confuse myself.

Search This Blog

Sunday, August 16, 2020

Intergenerational Trauma

I heard this term last year in the context of the Oklahoma Massacre, but it resonated strongly after I recently had a chat with a Chinese friend who emigrated to Singapore. We are roughly the same age, grew up mostly in the 1980s, and have postgraduate degrees. We have had a fairly comfortable middle-class life with large chunks lived outside of China (me in the US and her in Europe and Singapore). And yet, there are family behavioral and psychological patterns that are detached from reality and eerily similar not only between the two of us but are widespread among Chinese immigrants of my generation --- the generation that are not directly affected by but nevertheless in the shadow of the traumatic years from the 1950s to 1976, when daily life was not normal for our parents. Numbers, documents, history accounts, and words cannot accurately describe the emotional experience of the generation(s) of Chinese people who lived through these years. Like soldiers who come home with PTSD, our parents rarely talked about it. Trauma defies language. And yet it is not unusual or unique among people around the world in history and in the present. I often wonder if people have to share an experience to understand each other --- truly and authentically understand and empathize. The answer is sometimes no and sometimes yes. The question remains whether and how much people are both together and separate, which perhaps is and will always be a paradox. (I feel like I should quote GK Chesterton here but cannot remember the source or the exact wording.)

Tuesday, August 4, 2020

Angry Women and Their Books (1)

|

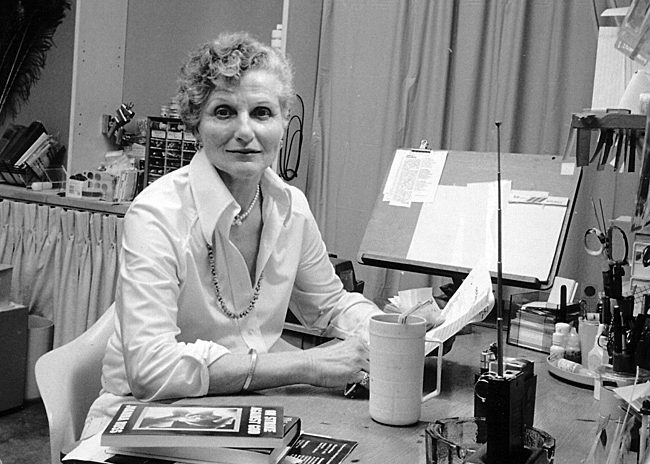

| James Tiptree, Jr. (Alice Sheldon) |

I must begin this discussion with Alice Bradley Sheldon, who wrote under the pseudonym James Tiptree, Jr. In particular, I recognized her anger in 2 of her stories --- Your Haploid Heart (1969) and The Screwfly Solution (1977). (Note: Spoilers of both stories below.)

Your Haploid Heart is the first Tiptree story I read. It puzzled me and tormented my mind. I knew the central conflict between the Esthaans and the Flenni, two manifestations of one species on the alien plant, is meant to refer to certain human qualities. I could feel it, but I could not figure out what it was.

All science fictions are allegories. All aliens are humans in disguise. Yes, even Arthur Clarke's gods.

In their misguided pursuit of becoming more human and more civilized, the Esthaans attempt to commit genocide of the Flenni, which is not really a genocide but rather "parricide, filicide ... perhaps suicide ..."

It was only after I read an article about the life and work of Alice Sheldon did I begin to understand. You see, she camouflaged her gender-related theme with descriptions of both "male" and "female" organisms in the strong and stocky Esthaans (the diploids) as well as the frail and beautiful Flenni (the haploids). Their codependence is established in that the Esthaans produce the Flenni in an asexual manner (while suggesting a certain disgust and fear of reproduction), and two Flenni (gametes) combine to give birth to Esthaans (but sex means death to them). Therefore, reading this story alone without context, it would be difficult to see that she was really talking about the perhaps-suicidal urge for men to destroy women.

But ...

Eight years later, after her male cover was blow, she unleashed her concerns of men killing women in The Screwfly Solution, under a female pseudonym Raccoona Sheldon. It is perhaps the most gruesome story I have ever read, even though the violence occurs off-stage. The cause of this massacre might be bizarre and alien, but the ideology used to justify it (i.e., purifying humanity from the corrupting effects of women's seductive power) is eerily familiar.

I think most every woman who has walked this earth can feel a shiver down her spine when she reads this story, because the threat of death is both literal and figurative.

Women are killed by men since the dawn of human society through today. It's not science fiction, it's reality. It's so common that we don't even talk about it. At least, nobody talks about it with any visible anger or shame.

Sure, women kill men too, at a fraction of the prevalence. And perhaps we can argue that men kill men the most, which is also true, although I don't know how that helps.

Figuratively, it is the dominance of male thought as the default, human thought, while female thought as "the other" and the aberrant and deviant.

Nevertheless ...

What Alice Sheldon wanted to point out is that men killing women is a form of human self-destruction.

This reminds me of a real exchange I read about between Cixin Liu and a history professor. Cixin Liu is a Chinese science fiction writer who won the 2015 Hugo Award for his novel "The Three-Body Problem" and has a massive following among Chinese (mostly male) science fiction readers. In 2007, at some public event, Liu and Professor Xiaoyuan Jiang had a debate about culture and cannibalism. Liu pointed to a young woman who was hosting this event and said, if the 3 of us were the last ones left to carry on human civilization, and we have to eat someone to survive, would you eat her? (Note that he went straight to the question "Would you eat HER?") Jiang replied, of course not. Liu said, we live in an indifferent universe (an idea he no doubt "learned" from Clarke). If you don't eat her and survive, you would be responsible for losing all of this glorious culture, think Shakespeare, Goethe, Einstein ... You think I'm cruel, but I'm only rational.

I'll leave you to ponder the irony of Mr. Liu's rationality.

Saturday, August 1, 2020

Primer

It is perhaps because a friend and I discussed the fear of death and dying this morning that I decided (finally) to rewatch this movie after over a decade. Even though I had read and watched a number of variations on the time-travel theme, I was very impressed by this little indie movie to remember it over the years. It's more interesting than the tropes and the done-to-death "solutions" to the fundamental paradoxes, for example, the reliance on coincidences and characters' unawareness in stories like "12 Monkeys". (I'm not saying "12 Monkeys" is bad, but I found it unsatisfying and tiresome, certainly not as clever as it thinks it is.)

Upon the second viewing, I am again impressed by Shane Carruth's courage to at least try to face the paradox of time travel. Of course, it inevitably breaks down as the lead characters' little scheme to prevent paradoxes breaks down later in the story. In general, his choice to let paradoxes happen and let history be rewritten in the way time travel happens in "Palimpsest" (a novella by Charles Stross) is audacious. Unfortunately he kind of lost control of the story and chickened out of the inevitable confrontations --- perhaps because of the lack of budget for special effects --- led to an ultimately disappointing ending.

The particular wrong turn in the script is the sudden appearance of the third, "failsafe" machine that pops up when the story is written into a corner, leading to the problem of when the initial timeline (which leads to the disastrous appearance a second Thomas Granger, Abe's girlfriend's father) ceases to exist. If this timeline is killed the moment Abe goes into the "failsafe" machine on another floor, Aaron would have no opportunity to try to beat him with his own trip.

The hastiness of this third machine and Aaron's previously-unestablished scheme of bringing a machine back, etc., are a lot of hand-waving that somewhat diminishes the story. Of course, the inherent paradoxical nature of time travel cannot be resolved, and this story always faces the unsolvable threat of "what if the original Abe or Aaron chooses not to go into the machine at 6 pm in the afternoon". Nevertheless, I am still a fan of this movie and Palimpsest for their creativity and courage to challenge cause and effect.

Recalling my discussion with the friend (who is, by the way, the least vain person I know), however, I realized that the emotional core of all the time-travel stories is regret and the unwillingness to accept ourselves for who we really are.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

The Ending of Le Samourai (1967), Explained

A quick online search after watching Jean-Pierre Melville's Le Samourai confirmed my suspicion: The plot is very rarely understood b...