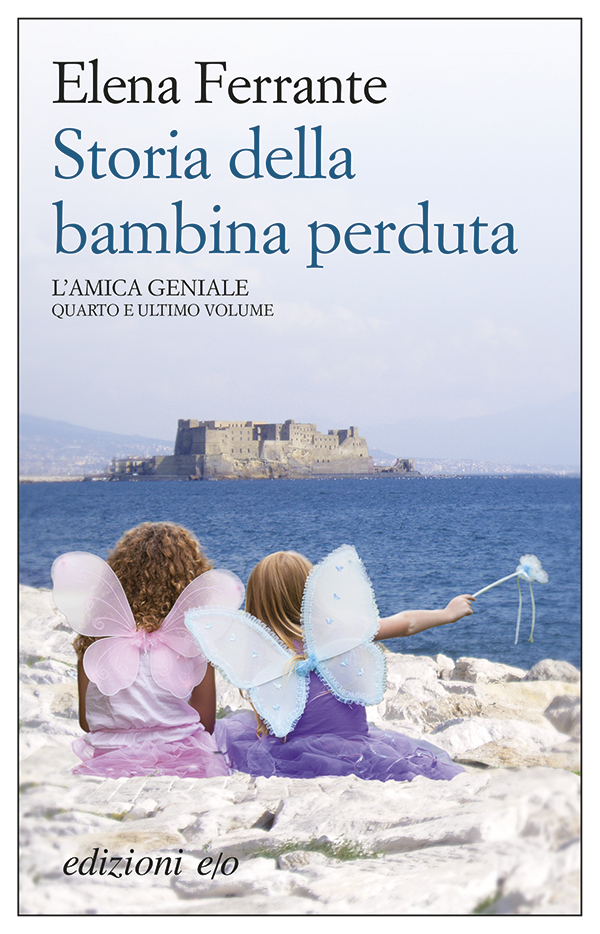

The large majority of this novel, minus the final third, has a very clear arc. With a series of unfolding events, we watch Lenu gradually drawn back to the neighborhood, as if led by irresistible fate, or was it her own unconscious desire?

Nino appeared once again out of the blue and triggered the destruction of the already-wobbly marriage between Lenu and Pietro. Lenu resisted going to Napoli to be near Nino for as long as she could, finding refuge with Mariarosa Airota and her current boyfriend (Lenu's old one) Franco. Things fell apart with Franco's death. The invisible hand pushed Lenu to Napoli. But still she resisted the call of the neighborhood for more than two years, living in an apartment in the affluent area, rented by Nino, and continuing her journalistic work. Thus, she could pretend that she was not circling closer and closer to ... home.

As sure as gravity, her orbit crossed with old friends and familiar faces. Alfonso, Carmen, then Lila ... Once Lila appeared in her life, Lenu's homecoming was inevitable. She held out for a little longer, until Nino's double life was revealed, and then his multiple lives surfaced. Meanwhile, Lenu's mother was dying. The journey home was so long and meandering that we hardly realized how insistent and inescapable it always was, but every change in her life pulled her closer to Lila and the neighborhood. Finally, she ended up in the apartment right above Lila's. Welcome home.

Throughout the slow and unconscious journey, Lenu continued her lifelong pattern of projecting her own unconscious motivations onto Lila. She constantly suspected that Lila was plotting to drag her back into the neighborhood and use her in Lila's own struggle against the Solaras, even when it was transparent to the reader that she was fighting with her own desire to go home. Such psychological insight is almost unexpected in an otherwise brutally candid first-person narrative, but we all know how everyone deceives herself all the time. We are all unreliable narrators, first and foremost to ourselves.

For the final third of the novel, however, we are shown the flip side of homecoming. Lenu would never completely belong to the neighborhood like Lila did, because she had left and built half of her identity in Pisa and Florence, with Adele and Pietro and the editors and publishers and academics. The non-Napoli part of herself was as deep and authentic as her Napoli part. In other words, one could go back, but one could never truly be back. The irreversible force is, of course, time.

Lenu stayed in the neighborhood for more than ten years, in part to protect and comfort Lila in her grief after the loss of Tina, and in part to further her own literary career. Eventually, she left again. Perhaps she finally accepted the reality that she could not entirely fit in Napoli or the neighborhood. No amount of physical attachment can change the mixture in her identity. In the new era, she was as much a stranger in Napoli as she was in Milan or Turin.

--------

After reading about Elena Ferrante's essays mentioning her admiration for Stanislaw Lem, I can't help but wonder how much Lem influenced her. One of the themes in Solaris is the unknowability of an alien entity, which lately I often compare to the unknowability of other people's mind. Humans do talked to each other and can know a little about each other, but the vast majority of our hearts and minds remain outside of each other's understanding.

In the last book of the quartet, more than any of the previous novels, we are reminded how little we know each other, even our best friends. Lila's actions as well as thoughts and intentions were always just outside of the edges of Lenu's view (one should note that it is by design). From the bits of clues and hints dropped here and there, the reader can piece together a thread of events with a heavy dose of conjecture. Lila's shocking decision to go work for Michele Solara in the previous novel was not some kind of capitulation to money or prestige. She gathered a massive amount of evidence and data on the Solara criminal enterprise, hoping to send them to jail one day. That effort failed because the criminals were rich, powerful, and deeply connected with other powerful networks throughout the political and economic landscape, above and under ground (or as the Chinese say, 黑道白道). (Sidenote: What a surprisingly relevant observation in current events in a totally different country!) The law could not touch them. For a while, Lila led a peaceful (on the surface at least) but fierce battle with the Solaras and gained an upper hand in the neighborhood. At some point, Pasquale assassinated the matriarch of the Solara family and caused massive chaos. Then the Solara brothers fought back and killed Alfonso, one of Lila's foot soldiers, and regained the upper hand. They were likely responsible for the abduction of Tina, for which Pasquale exacted revenge by killing them. Lila and Pasquale were tragic heroes that fought with the Solara family for years, perhaps decades, and paid a heavy price.

But that's an entirely different story, one that the author chose not to tell directly. Everything explicit in that story is left out of this one, leaving the reader with nothing but hearsay and innuendo. Perhaps such a story could not be told without a feeling of sensationalism, or perhaps the author does not want to erase the fantastical impression by giving it the full treatment. Either way, it does not belong in this novel.

--------

The disappearance of a child, in particular, a daughter, is obviously of great symbolic meaning to Ferrante, who wrote another novel, The Lost Daughter. There are many possible interpretations of this cataclysmic event in the quartet. In some ways, this is the beginning of Lila's disintegration. If we view Tina as a part of Lila (in a way all children are or used to be a part of their mothers), then her disappearance is a concrete loss of her body and self. In her enormous grief, she discarded her work and connections to the community and her battle for its soul. I see her subsequent wandering in time and space around Napoli as her way of scattering herself around the city, melting and dissolving into the city from which she was never able to leave, perhaps taking possession of it.

Once could also interpret Tina's kidnapping and probable murder as the patriarchy's violence to erase women, especially on those who refuse to erase themselves. Perhaps the loss of a child is the loss of hope and possibilities. In a city that is old and tired, typified by but not limited to Napoli, the loss of children or youthfulness reflects the calcification of culture and mind, leaving only an ever-shrinking path toward change and progress. The old order would rather go down the road of decay and death than loosing its grip on power for a terrifying new order. This fits with a general sense of lost opportunities since the social movements in the 1960s and 1970s, as the entire world reverted to its relentless conservativism and capitalism for the next half century. For a moment there was a glimmer of hope (or illusion?) of real historical change, but it was quickly snuffed out by the power that be.