I was just looking it up again for something on Edmund the bastard, and it occurred to me that this is one of the more readable plays; I hardly needed to look at the annotations. Then I somehow semi-consciously ended up on the YouTube watching a lecture on the play. It was interesting and comfortably detached. At one point a student commented that the characters are all so one-dimensional and only Lear goes through a full spectrum of human emotions. The lecturer asked whether the student thought, for example, Goneril is a one-dimensional villain. The student was apparently unconvinced. Suddenly I felt air went out of my lungs as if being punched in the gut. In a flash I remembered how it was Regan and Goneril that immediately grabbed my sympathies when I first saw the RSC's production of King Lear on TV. It's terrifying how this play has such ferocious power over me.

(It's not just me who find redeeming points in the two wicked daughters. Jane Smiley wrote "A Thousand Acres" loosely based on them.)

For a while I thought perhaps "Antony and Cleopatra" is my favorite. I love Othello and Much Ado as well. But after all this reminds me King Lear does something to me like nothing else.

Books, movies, food, and random thoughts in English and Chinese. Sometimes I confuse myself.

Search This Blog

Monday, May 23, 2016

Monday, May 16, 2016

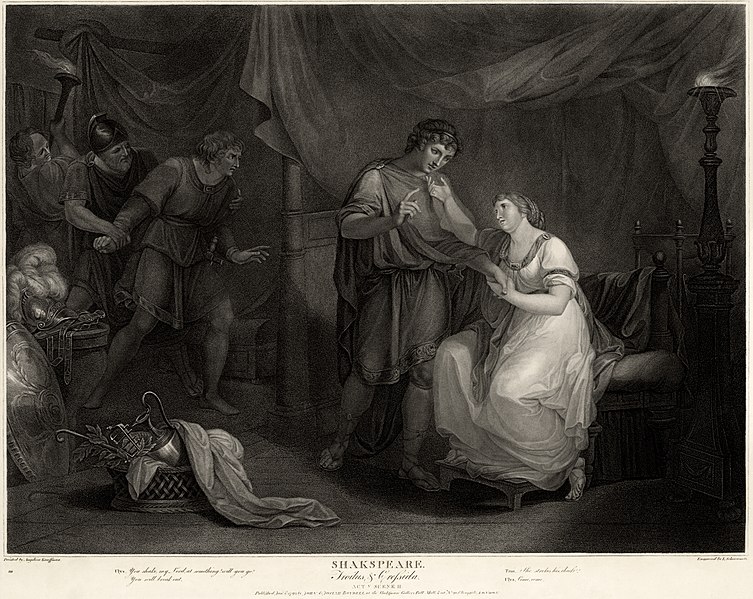

Troilus and Cressida

It's an odd play, even more of a "problem" than "Measure for Measure." If it weren't written four hundred years ago, one could safely file it under absurdism or postmodernism. Troilus and Cressida defies any conventional classification.

Just when I thought I knew Shakespeare, sort of, I realize I don't. Not at all.

It's a vicious takedown of the heroic and romantic mythologies. He is saying that, the truth of heroism is jealousy and stupidity, and the truth of romantic love is inconstancy and self-interest. It's unusually obscene and sexually explicit. It's roiling with a rage underneath all the bawdy jokes. It's unlike any other Shakespearean play, although the sneering view on war here could have come out of Falstaff's mouth.

How do the two strands of plot connect with each other? One is how two unwilling warriors, Achilles and Hector, finally come to a deadly confrontation. The other is a cynical revision of Romeo and Juliet. I don't know, but I feel in my gut that they do connect in some way.

Come to think of it, it's kind of funny how Shakespeare approached the classics, compared with, say, T. S. Eliot. Good ol' Willie obviously didn't worship the classics as the grandiose foundation of English literature. Rather, he trampled and shat all over the lofty ideals and glory. What a guy.

Friday, May 13, 2016

Greek References in ASOIAF

It so happens that I'm reading Troilus and Cressida lately --- I've never thought Greek tragedy could be done as farce --- while the Game of Thrones series just put on a flashback segment depicting the Tower of Joy.

The homage hits me between the eyes. I'm wondering why it took me so long to see the connection.

George RR Martin's references to Greek mythology are not nearly as abundant or apparent as those to Nordic mythology, the Wars of Roses, and Shakespeare, and they are hidden much deeper. So when I recognize one it is a bit of a shock.

I wrote about Deianira, wife of Hercules, being the inspiration for Daenerys Targaryen for the History Behind GoT site. Then, in Season 5 of the TV series, a plot is transparently lifted from Agamemnon's sacrifice of his daughter Iphigenia. I am not convinced that GRRM would choose to sail so close to the source material himself, but, alas, the TV series has given it away.

It is then all the more puzzling why I did not think of Lyanna Stark as the face that launched a thousand ships. Maybe because the warring factions fought on land? Obviously, men fighting over women is nothing new or unique to the Trojan war. Heck, even the Chinese history books are filled with stories like this. But something in Lyanna's story matches Helen's.

Even now, after 5 books and 5.5 TV seasons, after multiple characters have mentioned Lyanna over and again in their thoughts and their dialog, we still have no idea what happened from her perspective. The questions about Lyanna are almost exactly the same as those about Helen. Was she abducted or seduced? Was she raped or in love? Did she go willingly? Why? Did she regret it? Shakespeare and most interpretations believe Helen eloped with Paris out of love, and that is the sentiment of most ASOIAF readers on Lyanna as well. But we never get to hear it from the woman herself.

What links Lyanna to Helen of Troy is not their role in the Trojan war or Robert Rebellion, that the desire to take them in possession spiraled out of control and led to the slaughter of thousands. Rather, it's how they are both at the center of the myths and completely invisible. I don't know if GRRM is going to eventually reveal the true face of that face or stick to the homage and critique of the original myth and hide it to the end.

|

| Game of Thrones, S6E3, Tower of Joy. |

The homage hits me between the eyes. I'm wondering why it took me so long to see the connection.

George RR Martin's references to Greek mythology are not nearly as abundant or apparent as those to Nordic mythology, the Wars of Roses, and Shakespeare, and they are hidden much deeper. So when I recognize one it is a bit of a shock.

I wrote about Deianira, wife of Hercules, being the inspiration for Daenerys Targaryen for the History Behind GoT site. Then, in Season 5 of the TV series, a plot is transparently lifted from Agamemnon's sacrifice of his daughter Iphigenia. I am not convinced that GRRM would choose to sail so close to the source material himself, but, alas, the TV series has given it away.

It is then all the more puzzling why I did not think of Lyanna Stark as the face that launched a thousand ships. Maybe because the warring factions fought on land? Obviously, men fighting over women is nothing new or unique to the Trojan war. Heck, even the Chinese history books are filled with stories like this. But something in Lyanna's story matches Helen's.

Even now, after 5 books and 5.5 TV seasons, after multiple characters have mentioned Lyanna over and again in their thoughts and their dialog, we still have no idea what happened from her perspective. The questions about Lyanna are almost exactly the same as those about Helen. Was she abducted or seduced? Was she raped or in love? Did she go willingly? Why? Did she regret it? Shakespeare and most interpretations believe Helen eloped with Paris out of love, and that is the sentiment of most ASOIAF readers on Lyanna as well. But we never get to hear it from the woman herself.

What links Lyanna to Helen of Troy is not their role in the Trojan war or Robert Rebellion, that the desire to take them in possession spiraled out of control and led to the slaughter of thousands. Rather, it's how they are both at the center of the myths and completely invisible. I don't know if GRRM is going to eventually reveal the true face of that face or stick to the homage and critique of the original myth and hide it to the end.

Monday, May 2, 2016

War as Human Sacrifice (3): The Perpetuity of Violence

In the beginning of AGOT, the world is apparently in peace and prosperity. But even in this moment of peace, Ned's mind is filled with remembrance of war, Robert Baratheon's rebellion against the Targaryen dynasty only 14 years ago. Approximately a century ago was the Blackfyre Rebellion, a civil war that turned neighbors against neighbors and tore families apart. And soon enough Westeros will be embroiled in the War of Five Kings. Men are killed, women are raped, children lose homes, and grains are burned at the cusp of a long winter.

By the time we get to ADWD, the War of the Five Kings is over, but as the scope of the story pulls up like a camera, more battlefields and conflicts enter our view. Two mirror-image battles are waging with millions of lives promised to be lost: The battle of Winterfell between the Boltons and Stannis-led Wildling army and the battle of Meereen on land and sea. Plus the Iron Islanders are taking cities and castles along the west coast while Mace Tyrell's armies are sitting on a barrel of explosives in a standoff with the now-armed church. Oh, and let's not forget (even though the TV series have) the Golden Company and Prince Aegon who have taken Storm's End, the last we heard.

This is a question that applies to the real world much more than fiction: Is human history one of perpetual wars, with brief respites of temporary but unstable peace? Or are we more inclined to live in peace and periods of war are the anomaly? Given that we are living in a stretch of time that has not seen a world war for 70 years, it seems like we are moving in the direction of peace. American people are even luckier than others, as the United States has not seen armed conflicts on its own soil for 150 years. However, if we pull up the camera to cover a larger scope, the picture changes. Even now we are looking at a state of interminable military involvement. Since 1945, US has been directly involved in the Korean War in the 1950s, the Vietnam War in the 60s to early 70s, the first Gulf War in the early 90s, the second Gulf War in the early 2000s. The frequency is approximately the same as that in Westeros history, if not higher. We cannot go through even one lifetime without bloodshed, it seems.

In ASOIAF, even when one area (eg, Dorne or Highgarden) is teetering on a vicarious peace, war is raging somewhere else in the Westeros. While we can live in the illusion of peace in our daily lives, we are nevertheless involved in armed conflicts one way or another. For instance, we are all complicit as our tax dollars go into this drone and that bomb. No US president has ever not given orders to kill someone, and therefore our votes are also implicated.

The optimistic Steven Pinker believes that the better angels of our nature are winning in the long run, evidenced in the diminishing proportion of violent deaths over time. I am not in the position to judge whether this hopeful trend holds in the next centuries or whether the recent era is just another blip of peace in our violent history. Regardless, I think one can hardly deny that our nature is not a blank piece of paper and that violence is an integral part of it.

I'm very reluctant to label our violent tendencies as the "worse devils" of our nature. Few would admit that they like violence or enjoy killing, but there must be something deeply irresistible that leads us to warring with each other. It's almost like wars are a home for our spirit. We try to stay away from it and avoid any mention of it, and may even succeed for some years or some distance, but sooner or later we cannot help but return to it. Why? Chris Hedges says, War is a force that gives us meaning. His point is that nothing can bind people's (especially men's) spirit together and fend off the existential loneliness like war can. Sigmund Freud credits the Death Drive, which is as strong as the drive to survive. Whatever it is, I'm not sure it's something that can be easily erased from the depth of humanity, or that it should be.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

The Ending of Le Samourai (1967), Explained

A quick online search after watching Jean-Pierre Melville's Le Samourai confirmed my suspicion: The plot is very rarely understood b...